BBPlus is proud to work with UCL MA in Publishing students and to showcase a selection of their work. This will be the first of a series of blog posts.

Here is an opportunity to gain an insight into Publishers V Platforms from 2022 student Marisa Brand

Platforms vs. Publishers: A Distinction Without A Difference?

An Exploration of Section 230

By Marisa Brand May 2022

Framework, Scope & Methodology

The below paper seeks to address the salient ‘publishers’ versus ‘platforms’ debate surrounding internet-based social media companies. My aim is to explore definitions of ‘platforms’ and ‘publishers’ to inform a discussion on current policies as well as contribute to the dialogue on potential future regulatory efforts. Hence, I ask:

- How are ‘publishers’ and ‘platforms’ defined? Does this distinction matter?

- What oversight and regulatory efforts legislate these services?

- What changes to oversight and regulation are industry and policy stakeholders considering?

- What are the implications of this debate for book publishers?

This paper is primarily focused on US policy, for which the most research is available and the author has direct knowledge of, and the below discussion is informed by a mix of gray and academic literature. Though, interestingly, of the 37 articles I read for initial research, only two mentioned book publishers as part of the discussion.

Introduction

Over 4.62 billion people worldwide use social media, with more than 75% of the world’s population aged 13+ using social media and a staggering 93% of active internet users logging into social media sites regularly.1 Facebook is worth $200 billion, Twitter $49 billion, and Alphabet $2 trillion.2 Many experts argue that all of this is possible because of 26 simple words included in a piece of U.S. legislation passed in 1996 meant to keep the internet free of indecent content—Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA). Passed in the internet’s nascent days and influenced by the Californian Ideology of a new Jeffersonian democracy cultivated by an unfettered cyberspace,3 this legislation ultimately fostered the creation of the modern social network.

Throughout political, industry, and academic discussions about the role the internet plays in our day-to-day lives a recurring salient debate is this concept of ‘platforms’ vs. ‘publishers.’ The connotative distinction is that platforms are neutral hosts and thus are not responsible for the content hosted on their sites while publishers directly shape the content they produce and thus have ethical, social, and legal responsibilities for this content. However, in reality, the distinction—if there even is one—and its implications are far murkier than this. In turn, the regulatory and oversight efforts that apply to companies that fall into these categories have been developed through a limited, piecemeal approach and are open to many interpretations.

While this debate is generally in reference to news publishers and often leaves book publishers out of the mainstream conversation, it has relevant implications for the general trade publishing. From increased competition in the content space to discussions of free speech and censorship to the sway Goodreads has over readers, this conversation has far-reaching effects and is an area of debate and legislation the publishing industry should be following closely.

Exploring Definitions

The classification of social media companies as either ‘platforms’ or ‘publishers’ is a hot topic with both the political class and mainstream users of social networks. While nearly half of the articles I read for this paper had some version of the phrase ‘Publishers or Platforms’ in their titles, there was no clear, universal understanding of the breakdown between these categories. As Lydia Laurenson concludes in her Harvard Business Review article, “The [understood] differences are largely cultural.”4

While there is no legal definition of a platform in the US, the House of Lords and an EU contingency developed a working definition of online platforms during a 2016 Commission study: “An ‘online platform’ refers to an undertaking operating in two (or multi)-sided markets, which uses the Internet to enable interactions between two or more distinct but interdependent groups of users so as to generate value for at least one of the groups.”5 However, this definition is so broad that it generally proves unhelpful. A review of additional gray and academic literature found that the main colloquial difference between the two categories is the editorial role a company plays in the development, curation, and/or publication of the end content.

| Platforms | Publishers |

|

|

Table 1: Definitions of ‘platforms’ and ‘publishers’ as sourced from gray and academic literature

When social media companies were first founded, they could squarely fit in the ‘platform’ category, but with their human-developed curatorial algorithms, news cycle-influenced content moderation decisions, forays into the world of news delivery, data brokering efforts, and advertising commercial interests, they’ve moved far beyond this static role of an online intermediary. It is especially the editorial and influential nature of these companies’ algorithms that firmly move them out of a ‘neutral distributor of information’ category.11 Meanwhile, ‘publishers’ are also stepping outside their traditional roles, utilizing new technologies to step into the ad game and developing infrastructures that allow for the collection and hosting of user-generated content. As Napoli and Caplan discuss in their First Monday article, there is a convergence of traditional and digital publishing and distribution streams that lends to a recasting of editorial gatekeeping.12

In fact, the clunky term ‘platisher’—a company that “attempts to be both a destination for edited, themed content and a tool others can use to create content”13—was coined to describe the blurred lines between these two categories. Personally, I would argue that social media companies have ‘platforms’ but the full scope of their business operations cannot be defined by using the word ‘platform.’ Rather, I support using some variation of the phrase “digital media company” to apply to businesses that act in the above capacities.

Ultimately, though, the polarizing discussion surrounding the semantics of this classification is superfluous.14 It wasn’t until 2016 that Big Tech began making orchestrated public efforts to align their companies with the term ‘platform’ in an effort to portray a hands-off approach to content moderation.15 This is likely in direct response to increased scrutiny in Washington even though the word ‘platform’ does not actually appear in any relevant legislative context, which will be explored in more depth in the next section.

The Current State of Regulation

The United States & Section 230

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act passed in 1996 has been attributed with enabling the creation of the internet as we know it today. In the 1990s, there were two defamation court cases brought against early internet services—one who moderated content and one who did not—based on hosted third-party content. The Court ruled the service that did not moderate its content was the electronic equivalent of a bookstore,16 meaning the site was afforded the same protections as distributors17 and not held liable. Meanwhile, it was ruled that the service who moderated its content forfeited distributor liability and was thus held liable for the defamatory user-generated content in the same way a publisher would be. The bipartisan co-sponsors of Section 230 wrote the statute18 with the aim to overturn this precedent that online services could reduce liability by not moderating their content.

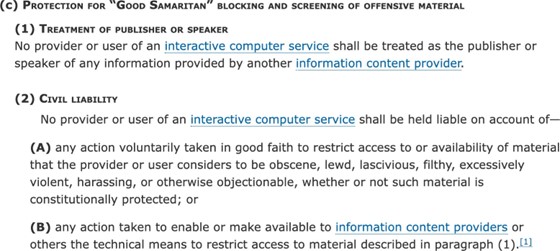

Full text of Chapter V: Wire or Radio Communication—Section 230(c) of the CDA as passed in 1996.19

The purpose of this legislation was to encourage ‘interactive computer services’ to actively moderate, curate, and edit their sites—especially as it relates to obscene content—without fear of legal liability. Essentially, this means that services who host user-generated online content are not held liable for the content of third-party posts, regardless of if they choose to remove or edit said content.

Contrary to the salient political commentary surrounding internet regulatory efforts, ‘platforms’ and ‘publishers’ are afforded the same protections under this pivotal piece of legislation; it is a differentiated classification with no legal bearing. The term ‘platform’ appears nowhere in this guiding piece of legislation and wasn’t referenced in judicial interpretations of the law until 2004, in which it was simply used as a term interchangeable with the word ‘website.’20 Rather, US Code 47 defines ‘interactive computer service’—the actual term that is referenced in Section 230—as:

Any information service, system, or access software provider that provides or enables computer access by multiple users to a computer server, including specifically a service or system that provides access to the Internet and such systems operated or services offered by libraries or educational institutions.21

This term could be interchangeable with countless other phrases such as website owners or online intermediaries, and the broad definition means that the law equally protects social media networks, news outlets with online comment forums, academic journals with third-party sourced content, and so on. The above legislation also does not include any stipulation that this active moderation must be neutral.

Additional context included in this bill indicates a view of the internet that is directly informed by the technological determinism school of thought championed by supporters of the Californian Ideology. Section 230(a) states that Congress finds the Internet “represents an extraordinary advance [and] offers a forum for a true diversity of political discourse, unique opportunities for cultural development, and myriad avenues for intellectual activity.”22 Further, Section 230(b) states, “It is the policy of the United States to promote the continued development of the Internet [and] to preserve the vibrant and competitive free market [...] unfettered by Federal or State regulation.”23

Section 230 accomplished just that, creating an environment in which interactive computer services were able to build and expand unrestrained by bureaucracy and without a common law duty-of-care consideration. It wasn’t until 2018 that the first updates to guidance on the legislative application of Section 230 were made since it was enacted in 1996. With the passage of the anti-sex trafficking FOSTA bill in 2018, an exemption was added to Section 230 decreasing legal protections for ‘computer services’: “Section 230 doesn’t apply to civil and criminal charges of sex trafficking or to conduct that ‘promotes or facilitates prostitution.’”24

Global Regulatory Measures

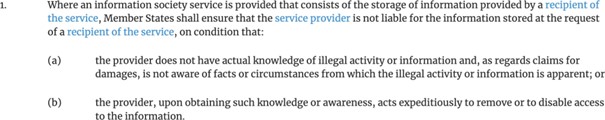

The UK and the EU enacted a similar liability protection to encourage online content moderation through Article 14 of the 2000 e-Commerce Directive.

Text of EU Article 1425

The UK is working to determine under which governmental body oversight should fall to and the EU is focused on guaranteeing data privacy and curtailing the influence these companies’ ad services have over consumers. In a blow to BigTech, legislation was passed in Australia in 2021 requiring Facebook and Google to pay publishers for news hosted on their platforms26 in an effort to demystify their news algorithm processes and compete more fairly in the marketplace. In Africa, political circumstances have contributed to an environment in which individual users rather than the host companies are held responsible for content.27

Moving Forward

Regardless of a ‘platform’ or ‘publisher’ classification, social media companies are performing activities far beyond the scope of ‘interactive computer services.’ Enabled by Section 230, these companies have been allowed to grow exponentially over the past two decades while not being held accountable legislatively. Clouded by the glow of technological determinism, lawmakers in 1996 failed to consider the sheer negative influence and power to harm these companies could wield,28 ultimately resulting in harmful outcomes such as Russian interference in the 2016 US Presidential Election and the facilitation of terrorist recruitment campaigns. It is time to carefully consider what can be done to curb the negative effects that arise from an unrestrained social network landscape.

The difficulty of regulating and monitoring this area—and perhaps an explanation for why this is a debate we’re only getting to two decades after the creation of social networks—is the novel, global, and constantly evolving nature of the internet. As one legal expert points out, this debate “lends itself to unique thinking about the right mix of private and public regulation.”29

Public Regulation

In the US, lawmakers are taking a piecemeal approach to narrowing the scope of Section 230 and imposing more stringent oversight on companies like Facebook. This is a very party-driven issue, though, with Democrats exploring legislation to better control dangerous and hateful content while Republicans are looking for solutions to guarantee neutrality and minimal censorship by algorithms. Legislative pieces to watch are highlighted in the below table.

|

Proposed Legislation |

Effect |

Critique |

|

SAFE TECH Act |

This would make services liable for any paid advertising content posted to their sites that is deemed offensive and used to target vulnerable people. |

far-reaching implications for the internet economy |

|

PACT Act |

This would require websites to transparently report how they moderate the content on their sites while also requiring companies to remove posted illegal content and activity within 24 hours. |

|

|

EARN IT Act |

This would act as a bargaining chip, granting liability protection only to those services that could demonstrate they were fighting child sex abuse. |

|

|

Protecting Americans from Dangerous Algorithms Act |

This would remove liability immunity for a site if its algorithm is used to amplify content directly relevant to a case involving civil rights breaches and international terrorism. |

|

Table 2: Overview of relevant legislative pieces; Sourced from The Verge, HBR, and the Atlantic

However, I believe a more direct change to the language of Section 230 imposing a duty-of-care approach would be more impactful for regulating runaway social media companies. For example, one legal scholar recommends the addition of the highlighted words to Section 230 to more clearly hold ‘interactive computer services’ accountable for reasonable content moderation and encourage thoughtful platform design and implementation:

No provider or user of an interactive computer service that takes reasonable steps to address known unlawful uses of its services that create serious harm to others shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider in any action arising out of the publication of content provided by that information content provider.30

Another possible approach to language change is changing the term “information” in the original statue to “speech” and factoring in the intent behind the published content—a modification supported by another legal school of thought:

No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information speech wholly provided by another information content provider, unless such provider or user intentionally encourages, solicits, or generates revenue from this speech.31

Updates to the language of Section 230 like those outlined above would uphold the original intent behind the legislation while factoring in how modern ‘interactive computer services’ operate. By narrowing the scope of the regulation, companies’ liability protections will remain intact while they are made to take a more active role in moderating harmful content and illegal or unethical transactions taking place on their platforms. As for limitations of a private approach, legislative bodies are slow-moving and not well equipped32 to handle this emerging technological domain.33 And, as this transcends borders, there is unlikely to ever be universal consensus on regulatory efforts.

Private Efforts

While these policy debates drag on, there are both top-down private efforts that should be considered. Recently, companies appear to be taking both individual and industry-wide steps to address many of the issues surrounding their platforms.

In 2020, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube signed on to the Global Alliance for Responsible Media (GARM), “a cross-industry initiative to create a common set of definitions for hate speech and other harmful content and an independent audit of how the platforms deal with this type of content.”34 Mark Zuckerberg has commented that “it may make sense for there to be liability for some of the content [on Facebook]” and the company has taken steps to establish standardized content review processes and increase transparency around these decisions by establishing the Independent Oversight Board.35 While Twitter implemented measures throughout the past two years to take on more responsibility for the content hosted on their platform, Elon Musk,36 the site’s new owner, is a technological determinist who has vowed to return the service to its roots as a neutral platform. It is yet to be seen if these proposed algorithm shifts would actually decrease the influence the company has over what users see, effectively making the platform more ethical, or if this is a PR stunt to shirk any responsibility they may hold for fostering and perpetuating harmful content.

Ultimately, company-initiated digital literacy educational campaigns and proactive transparency about company’s algorithms and content moderation processes would be necessary to ensure corporate accountability and establish a more ethical relationship between interactive computer services and their users. As for the limitations of a private approach, commercial interests and monetary motivations can influence and cloud corporate decision making. And, as we’re seeing play out, a change in leadership or shifting whims of a company’s board can effectively eradicate any progress overnight.

Implications for the Publishing Industry

The general trade publishing industry is not just competing with TV and movies for consumers’ attention anymore. From podcasts to YouTube to endless social media feeds, the internet has exponentially increased the amount of content targeted at consumers. The publishing industry should be aware of the free reign content competitors like social media sites have been given by governments. While they’re adhering to clear regulations and liability expectations, this new class of competitor has had unfettered access to billions of users, which is ultimately an unfair marketplace competitive advantage. In March 2022, the UK Publishers’ Association joined a coalition of major media businesses to send a letter to the Prime Minister, stressing the importance of advancing oversight efforts and the need to urgently “tackle the harmful impact of tech platforms on UK media and publishing.”37 A response to this call for action is expected in May 2022.

Debunking the belief that algorithms are neutral tools raises questions about the use of algorithms in the publishing space. One major example is the “social cataloging” site Goodreads. Owned by Amazon, Goodreads not only forces users to forfeit all rights to content they publish—often without realizing this a part of the privacy terms—but their “black box” algorithms perpetuate cultural echo chambers and exploit reader data for commercial gain.38 While this is known as an extremely influential platform in the book world, Goodreads is far from being the simple “social cataloging” site it’s positioned as, and its nefarious underside should encourage publishers to reconsider their interactions with the site.

Depending on where this broader conversation goes and what regulation—if any—is ultimately implemented, publishers may also want to consider the ethics of housing corporate accounts across these channels and utilizing user content generated through free labor for their own commercial gain. Additional food for thought stems from the commissioning process; when commissioning a manuscript or signing an author based on trending social media data, editors should stop to think how the popularity of this topic or voice was influenced by biased algorithms.

Conclusion

Once we take a closer look, the distinction between these two business model types begins to erode. In today’s reality—where social platforms have editorial algorithms and publish their own content and traditional publishers have migrated to the internet with some even launching their own user platforms—this becomes a difference without a distinction. But ultimately in terms of the current regulatory environment, trying to parse the minutiae between these words is simply a marketer’s game. It’s the internet factor that makes a difference, not the murky distinction between ‘platforms’ and ‘publishers.’

As we move forward, social media companies and other interactive computer services will only continue to grow further beyond the scope by which they are legislated by in Section 230. As such, it is time to narrow liability protections and investigate additional legislative measures to hold these companies accountable. The most effective and efficient way to ensure responsibility and accountability will be through a dual private-public approach, and these efforts should begin with increasing transparency and education around algorithm-driven content moderation.

References

1 Claire Beveridge, ‘150+ Social Media Statistics That Matter to Marketers in 2022’, Hootsuite Blog, 2022

<https://blog.hootsuite.com/social-media-statistics-for-social-media-managers/> [accessed 22 April 2022]. 2 These valuations dropped drastically in the last several weeks due to S&P fluctuations and stakeholder hesitancy.

3 Cameron Barbrook, ‘The Californian Ideology’, Mute (Mute Publishing Limited, 1995)

www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/californian-ideology> [accessed 28 April 2022].

4 Lydia Laurenson, ‘Don’t Try to Be a Publisher and a Platform at the Same Time’, Harvard Business Review, 19 January 2015

https://hbr.org/2015/01/dont-try-to-be-a-publisher-and-a-platform-at-the-same-time [accessed 3 May 2022].

5 Online Platforms and the Digital Single Market, 2016

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201516/ldselect/ldeucom/129/12906.htm [accessed 2 May 2022].

6 Laurenson.

7 Aarthi Vadde, ‘Platform or Publisher’, PMLA, 136.3 (2021), 455–62

https://doi.org/10.1632/S0030812921000341

8 Alexis C. Madrigal, ‘The “Platform” Excuse Is Dying’, The Atlantic, 11 June 2019

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/06/facebook-and-youtubes-platform-excuse-dying/591466/ [accessed 20 April 2022].

9 David Greene, ‘Publisher or Platform? It Doesn’t Matter.’, Electronic Frontier Foundation, 2020

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/12/publisher-or-platform-it-doesnt-matter [accessed 16 April 2022].

10 Laurenson.

11 Simone Murray, ‘Secret Agents: Algorithmic Culture, Goodreads and Datafication of the Contemporary Book World’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, 24.4 (2021), 970–89

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1367549419886026

12 Philip Napoli and Robyn Caplan, ‘Why Media Companies Insist They’re Not Media Companies, Why They’re Wrong, and Why It Matters’, First Monday, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v22i5.7051

13 Laurenson.

14 Perhaps, if pundits are intent on analyzing terminology, they should dig into the possible classification of social media companies as ‘common carriers’ rather than focusing on a term that has no legitimate legislative implications.

15 Greene.

16 Adi Robertson, ‘Why the Internet’s Most Important Law Exists and How People Are Still Getting It Wrong’, The Verge, 21 June 2019

https://www.theverge.com/2019/6/21/18700605/section-230-internet-law-twenty-six-words-that-created-the-internet-jeff-kosseff-interview [accessed 29 April 2022].

17 Liability protection was granted to distributors (e.g. bookstores, libraries, and newsstands) following a 1950s Supreme Court case that found a Los Angeles city ordinance that led to the jailing of a bookstore owner for selling a book that contained erotic content to be unconstitutional. This ruling deemed that these institutions could not be held liable for the content in the books and newspapers they distributed unless they knew or should have known material was libelous, defamatory, or otherwise illegal.

18 For the full story behind the creation and consequences behind this legislation, read the 2019 book The Twenty-Six Words that Created the Internet by US Naval Academy law professor Jeff Kosseff.

19 Protection for Private Blocking and Screening of Offensive Material, U.S., 1996, TItle 47

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/47/230

20 Greene.

21 ‘Definition: Interactive Computer Service from 47 USC § 230(f)(2)’, LII / Legal Information Institute, 1996

<https://www.law.cornell.edu/definitions/uscode.php?width=840&height=800&iframe=true&def_id=47-US C-1900800046-1237841278&term_occur=999&term_src=title:47:chapter:5:subchapter:II:part:I:section:23 0> [accessed 27 April 2022].

22 Protection for Private Blocking and Screening of Offensive Material, TItle 47.

23 Protection for Private Blocking and Screening of Offensive Material, TItle 47.

24 Casey Newton, ‘Everything You Need to Know about Section 230’, The Verge, 28 May 2020

https://www.theverge.com/21273768/section-230-explained-internet-speech-law-definition-guide-free-moderation [accessed 27 April 2022].

25 ‘Article 14 Hosting’, Better Regulation, 2000 https://service.betterregulation.com/document/207184

[accessed 27 April 2022].

26 Shaimaa Khalil, ‘Facebook and Google News Law Passed in Australia’, BBC News, 25 February 2021, section Australia www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-56163550 [accessed 28 April 2022].

27 Vincent Adakole Obia, ‘Are Social Media Users Publishers? Alternative Regulation of Social Media in Selected African Countries’, Makings Journal, 2.1 (2021)

https://makingsjournal.com/are-social-media-users-publishers-alternative-regulation-of-social-media-in-selected-african-countries/ [accessed 27 April 2022].

28 For more on the dangerous impacts these companies have on society, I recommend watching the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma and listening to the New York Times podcast Rabbit Hole. 29 Orly Lobel, ‘The Law of the Platform’, MINNESOTA LAW REVIEW, 137, 2016

https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1136&context=mlr [accessed 10 April 2022].

30 Michael D. Smith and Marshall Van Alstyne, ‘It’s Time to Update Section 230’, Harvard Business Review, 12 August 2021 < https://hbr.org/2021/08/its-time-to-update-section-230 [accessed 27 April

2022].

31 Peter J. Pizzi, ‘Social Media Immunity in 2021 and Beyond: Will Platforms Continue to Avoid Litigation Exposure Faced by Offline Counterparts’, Defense Counsel Journal, 88.3 (2021)

<https://www.iadclaw.org/defensecounseljournal/social-media-immunity-in-2021-and-beyond-will-platform s-continue-to-avoid-litigation-exposure-faced-by-offline-counterparts/> [accessed 27 April 2022].

32 For example, this author sat in on a 2018 House of Representatives hearing on running a multi-year study on the Internet of Things to inform how Congress could legislate and advance the industry [H.R.6032 - 115th Congress - SMART IoT Act]. Not only had the first Alexa been sold a full four years prior but one Congressman spent his entire question period asking if smart speakers could be used by terrorists to start fires. Additionally, the average age of a US Senator is 64 years old.

33 ‘How Old Is Congress?’, Quorum, 2021

https://www.quorum.us/data-driven-insights/the-current-congress-is-among-the-oldest-in-history/ [accessed 2 May 2022].

34 Jo Adetunji, ‘Where Does the Buck Stop for Social Platforms When It Comes to Responsible Publishing?’, Journalism.Co.Uk, 2020

https://www.journalism.co.uk/news-commentary/where-does-the-buck-stop-for-social-platform-when-it-comes-to-responsible-publishing-/s6/a768021/ [accessed 20 April 2022].

35 Smith and Alstyne.

36 Partway through my writing of this assessment, Elon Musk purchased Twitter; for the sake of time and brevity, I was unable to weave the full implications of this development into other sections of this paper.

37 Omar Oakes, ‘Coalition of TV, Publishing and Radio Calls for Swifter Action on Big Tech Regulation’,

The Media Leader, 2022

<https://the-media-leader.com/coalition-of-tv-publishing-and-radio-call-for-swifter-action-on-big-tech/> [accessed 1 May 2022].

38 Murray.

Bibliography

Adakole Obia, Vincent, ‘Are Social Media Users Publishers? Alternative Regulation of Social Media in Selected African Countries’, Makings Journal, 2.1 (2021)

https://makingsjournal.com/are-social-media-users-publishers-alternative-regulation-of-social-media-in-selected-african-countries/ [accessed 27 April 2022]

Adetunji, Jo, ‘Where Does the Buck Stop for Social Platforms When It Comes to Responsible Publishing?’, Journalism.Co.Uk, 2020

https://www.journalism.co.uk/news-commentary/where-does-the-buck-stop-for-social-platform-when-it-comes-to-responsible-publishing-/s6/a768021/ [accessed 20 April 2022]

‘Article 14 Hosting’, Better Regulation, 2000

https://service.betterregulation.com/document/207184 [accessed 27 April 2022]

Barbrook, Cameron, ‘The Californian Ideology’, Mute (Mute Publishing Limited, 1995)

https://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/californian-ideology [accessed 28 April 2022]

Beveridge, Claire, ‘150+ Social Media Statistics That Matter to Marketers in 2022’, Hootsuite Blog, 2022

https://blog.hootsuite.com/social-media-statistics-for-social-media-managers/ [accessed 22 April 2022]

‘Definition: Interactive Computer Service from 47 USC § 230(f)(2)’, LII / Legal Information Institute, 1996

https://www.law.cornell.edu/definitions/uscode.php?width=840&height=800&iframe=tru e&def_id=47-USC-1900800046-1237841278&term_occur=999&term_src=title:47:chapte r:5:subchapter:II:part:I:section:230> [accessed 27 April 2022]

Greene, David, ‘Publisher or Platform? It Doesn’t Matter.’, Electronic Frontier Foundation, 2020

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/12/publisher-or-platform-it-doesnt-matter [accessed 16 April 2022]

‘How Old Is Congress?’, Quorum, 2021

https://www.quorum.us/data-driven-insights/the-current-congress-is-among-the-oldest-in-history/ [accessed 2 May 2022]

Khalil, Shaimaa, ‘Facebook and Google News Law Passed in Australia’, BBC News, 25 February 2021, section Australia <https://https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-56163550 [accessed 28 April 2022]

Laurenson, Lydia, ‘Don’t Try to Be a Publisher and a Platform at the Same Time’, Harvard Business Review, 19 January 2015

https://hbr.org/2015/01/dont-try-to-be-a-publisher-and-a-platform-at-the-same-time [accessed 3 May 2022]

Lobel, Orly, ‘The Law of the Platform’, MINNESOTA LAW REVIEW, 137, 2016

https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1136&context=mlr [accessed 10 April 2022]

Madrigal, Alexis C., ‘The “Platform” Excuse Is Dying’, The Atlantic, 11 June 2019

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/06/facebook-and-youtubes-platform-excuse-dying/591466/ [accessed 20 April 2022]

Murray, Simone, ‘Secret Agents: Algorithmic Culture, Goodreads and Datafication of the Contemporary Book World’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, 24.4 (2021), 970–89

https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549419886026

Napoli, Philip, and Robyn Caplan, ‘Why Media Companies Insist They’re Not Media Companies, Why They’re Wrong, and Why It Matters’, First Monday, 2017

https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v22i5.7051

Newton, Casey, ‘Everything You Need to Know about Section 230’, The Verge, 28 May 2020

https://www.theverge.com/21273768/section-230-explained-internet-speech-law-definition-guide-free-moderation [accessed 27 April 2022]

Oakes, Omar, ‘Coalition of TV, Publishing and Radio Calls for Swifter Action on Big Tech Regulation’, The Media Leader, 2022

<https://the-media-leader.com/coalition-of-tv-publishing-and-radio-call-for-swifter-action- on-big-tech/> [accessed 1 May 2022]

Online Platforms and the Digital Single Market, 2016

<https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201516/ldselect/ldeucom/129/12906.htm> [accessed 2 May 2022]

Pizzi, Peter J., ‘Social Media Immunity in 2021 and Beyond: Will Platforms Continue to Avoid Litigation Exposure Faced by Offline Counterparts’, Defense Counsel Journal, 88.3 (2021)

https://www.iadclaw.org/defensecounseljournal/social-media-immunity-in-2021-and-beyond-will-platforms-continue-to-avoid-litigation-exposure-faced-by-offline-counterparts/ [accessed 27 April 2022]

Protection for Private Blocking and Screening of Offensive Material, U.S., 1996, TItle 47

<https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/47/230

Robertson, Adi, ‘Why the Internet’s Most Important Law Exists and How People Are Still Getting It Wrong’, The Verge, 21 June 2019

<https://https://www.theverge.com/2019/6/21/18700605/section-230-internet-law-twenty-six-words-that-created-the-internet-jeff-kosseff-interview [accessed 29 April 2022]

Smith, Michael D., and Marshall Van Alstyne, ‘It’s Time to Update Section 230’, Harvard Business Review, 12 August 2021

https://hbr.org/2021/08/its-time-to-update-section-230 [accessed 27 April 2022]

Vadde, Aarthi, ‘Platform or Publisher’, PMLA, 136.3 (2021), 455–62